Financial adviser Pamela Capalad spends a lot of her time breaking down job offers and coaching clients on how to negotiate for a raise — and she finds those strategies especially important for people of color.

Income is one of the most important factors affecting how much money people can save for retirement, and Black workers in the U.S. earn less than their white counterparts. Black men with a bachelor’s degree, for example, earned 24% less than their white counterparts in 2019, according to a Conference Board report published last year. This discrepancy creates financial burdens both in the present and in the future, especially when it comes to retirement security.

“You need income that is in addition to what covers your bills,” said Capalad, a certified financial planner and founder of the advisory firm Brunch & Budget, based in Brooklyn, N.Y. “That’s one of the biggest issues for people of color — they’re paid less.”

But salaries are only part of the equation when determining a worker’s compensation, she added. Compensation also encompasses health insurance, life and disability insurance and retirement benefits, but seeing the big picture can be difficult for workers who are focused on getting ahead. A high salary alone may seem worth the job opportunity, even if other benefits are lacking.

“The tricky part — especially if you’re a person of color who has historically been paid less [and who is] offered so much more than you’re used to — is the temptation,” Capalad said.

The racial wealth gap

Wage inequality is one of the main reasons for the racial wealth gap in retirement savings, but there are also other important factors.

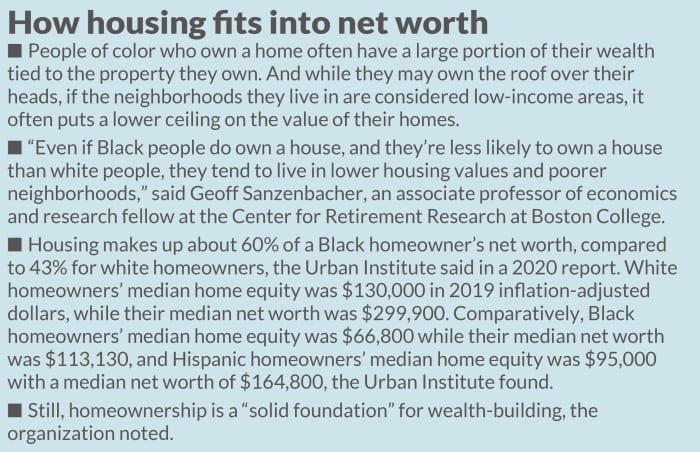

A home is one of the most valuable assets an American can have in their retirement, but people of color are less likely to be homeowners than their white counterparts.

While financial advice can help people overcome investment fears and find the right products to achieve retirement security, the lack of diversity in the financial-services industry creates barriers for people of color seeking sound financial advice.

Maintaining one’s health is also important for when it comes to financial security, yet there are significant barriers to receiving and affording healthcare in some minority communities, and medical debt disproportionately affects Black Americans. Many of these factors can be traced back to the long history of discrimination in America, which includes public policies that put people of color at a disadvantage.

Saving for retirement is a challenge for many Americans, but people of color tend to have fewer resources available for their post-working lives, data show. Many minority groups are more likely to have no retirement savings at all, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Nearly seven in 10 (68%) white Americans between the ages of 32 and 61 years old had money in a retirement account in 2016, up about 1 percentage point from 2007. Comparatively, 41% of their Black peers in that age bracket had retirement-account savings in 2016, down from 47% in 2007. That means about 6 in 10 Black families had nothing saved for retirement — at least not in employer-sponsored accounts such as 401(k) plans or in individual retirement accounts, as the EPI defined these savings.

Even three years in, it’s still too soon to understand the true economic impact the pandemic has had on Americans’ retirement preparedness. But there are a few indications that this extraordinary event has made the racial retirement-wealth gap worse. Black Americans were laid off at higher levels during the pandemic, and recovery in employment was slower for them thereafter, a RAND Corporation study found.

Other effects have already begun to ripple. People of color saw gains in homeownership rates decline after the pandemic, and they were also more likely to see a reduction in wages. Older people, people with chronic health conditions and people of color were also at higher risk of complications arising from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

A looming recession and higher rates of inflation have exacerbated the gap. The costs of everyday expenses like groceries and gas have climbed, and in an effort to curb inflation, the Federal Reserve has been steadily increasing the federal-funds rate, which makes borrowing money — such as for a mortgage or on a credit card — more expensive.

The repercussions of lower incomes

For Black households, the median income in 2021 was roughly $48,000, compared with a median household income for white non-Hispanic households of about $78,000, according to the Census Bureau. Hispanic households had a median income of about $58,000. For Asian households, median income was slightly more than $101,000.

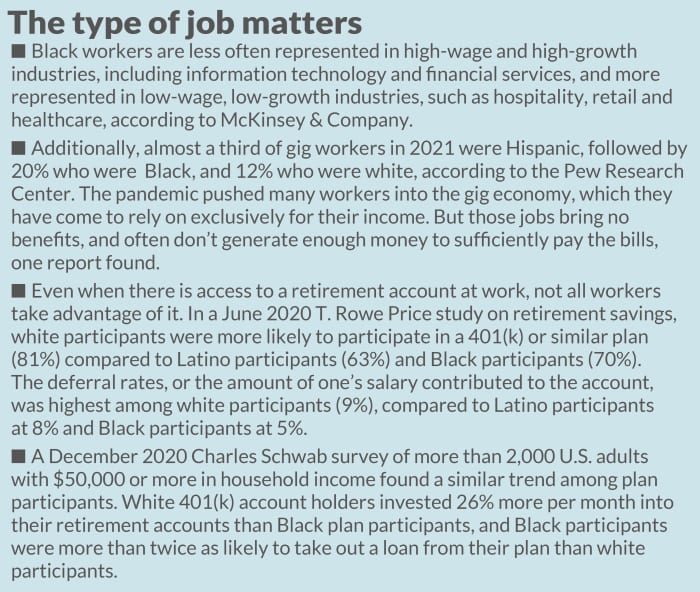

Research shows that labor discrimination has fueled that divide. White workers were more likely to have “good jobs” than their Black or Latino counterparts, even among those who had the same level of education, according to a 2019 report from JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. Good jobs were defined as those with “family-sustaining earnings” of $35,000 a year for workers between the ages of 25 and 44 and $75,000 for people with at least a bachelor’s degree.

“If you have very low levels of income, you have less discretionary income, and that means you have most of your money going to immediate needs: food, shelter, clothing, basic supplies,” said Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, chief of organizing, policy, and equity at National Community Reinvestment Coalition. “There isn’t as much to invest.” Those who do invest may have to be more conservative with their asset allocations in an effort to preserve their money, which then limits returns, he added.

Wage inequality has a lasting effect on retirement security, said Richard Johnson, a senior fellow and director of the retirement policy program at the Urban Institute, an economic and social-policy think tank. Even if lower-income workers contribute a substantial portion of their salaries to a workplace savings account — such as 15%, the level many financial advisers suggest — the total contribution amount will be lower because their salaries are lower. And regardless of how much they’re earning, their spending needs are still similar to those of other families.

Lower incomes can also lead to lower Social Security benefits, which are calculated using factors such as lifetime earnings and age at the time of claiming. Workers may also have to claim Social Security at a younger age (the earliest being 62), Johnson noted, either because of health problems or because they are no longer able to work in a physically demanding job. People who claim Social Security benefits before their full retirement age receive a lower benefit than if they had waited. The longer beneficiaries wait to claim, the more they get, up to age 70.

Because of their lower average earnings and the way Social Security benefits are calculated, Black Americans typically receive less than their white counterparts. Lower-wage workers do receive a larger share of their preretirement earnings due to the progressive formula the Social Security Administration uses, but it still comes out to a smaller dollar amount. For example, in 2016, Black beneficiaries received just over $9,280, compared with white Americans, who received roughly $11,610, according to the Urban Institute. Black Americans on average did receive more in Supplemental Security Income ($620 versus $300) and slightly more in public assistance ($40 versus $20), but had less in retirement income, interest and total earnings.

Social Security is a lifeline for many Black Americans. In 2014, only three in 10 Black Americans aged 65 or older had income outside of Social Security in retirement, such as from 401(k) savings or pensions, compared with 47% of white Americans, according to the National Academy of Social Insurance. Social Security was the sole source of income for one-third of Black Americans, compared with 18% of white Americans.

The barriers to homeownership

Through his family’s history, Denzel Tongue has seen just how difficult homeownership can be for Black Americans.

His mother grew up in West Oakland, Calif., moved away, and tried to save enough money for a home with a union job, but she was still priced out of the housing market when she returned to her old neighborhood to buy a home. Tongue’s grandfather, a U.S. Air Force veteran, had to settle for a home in West Oakland, then considered a “high lending risk” zone, because of policies and practices that kept Black buyers out of more desirable Oakland neighborhoods.

Despite those difficulties, Tongue, who works at the Alameda County Public Health Department, still hopes to purchase a home in the Bay Area one day. He has studied the hard lessons about the nation’s housing market for people of color — including inferior lending rates that prevent low-income people from gaining access to the capital they need to buy a home, as well as the marketing of predatory financial products, he said.

“Homeownership can be super tenuous in the Black community — there’s just a lot of obstacles to homeownership,” he said. “That being said, I still really love my hometown, would still love to live here, and my goal is to continue to save and hopefully own a home in the Bay Area.”

Redlining was a racially discriminatory practice that allowed lenders to deny mortgage services to applicants in predominantly Black and immigrant neighborhoods. It got its name from the red lines on maps that marked restricted areas that were deemed too risky for lenders. When the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was passed, redlining was outlawed, but its repercussions continue to reverberate — and some studies find the practice may still exist. The restrictions on homeownership, or the ability to buy homes in only certain less-desirable neighborhoods, has affected the capacity of people of color to bolster their retirement security and accumulate generational wealth.

Homeownership is a critical component of retirement security, and barriers to homeownership have helped widen the racial retirement gap for Black Americans, public policy experts say. That leaves many older Black Americans unable to tap into a key retirement asset, either from the sale of a home or through home-equity loans. Although inflated home prices are a burden for those looking to purchase property, it’s through gradually rising home prices that many people see their personal net worth increase.

“Homeownership is still the biggest asset the typical American will hold in their lifetime,” said William Rodgers III, vice president and director of the Institute for Economic Equity at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. But there are racial discrepancies when it comes to homeownership, and the value of homes owned by Black Americans lags behind that of white Americans, he said.

Black Americans saw a slower growth rate for homeownership during the pandemic, the Center for American Progress found — 44.1% at the end of 2020, just 0.1 percentage point higher than at the end of 2019. Comparatively, homeownership among white Americans rose from 73.7% to 74.5%. More Black homeowners than white homeowners also struggled to pay their mortgages during the pandemic — 17.6% versus 6.9% between August 2020 and March 2021.

During the pandemic, homeownership among Black households was also more volatile than white households. Black homeownership rose 3 percentage points in early 2020, then fell 2.9 percentage points. At the same time, white homeownership grew 2.3 percentage points in early 2020 and then dipped 1.5 percentage points, the Center for American Progress found.

An improvement in homeownership for people of color would not only narrow the homeownership gap among racial groups, but also the racial wealth gap in retirement savings overall — something that could have lasting effects for future retirees and the generations that follow them.

“It’s a generational linkage,” Tongue said. “People can’t pass on that generational wealth. It limits opportunities.”

The problem of medical debt

Medical debt is another barrier to retirement security, as is lack of quality healthcare and health insurance — which can be the cause of medical debt in the first place. Families with damaged credit or less money to spend on medical services and prescriptions may forgo necessary medical attention, potentially affecting their health now and in the future. “It is a vicious cycle,” said Signe-Mary McKernan, vice president for labor, human services and population at the Urban Institute.

Medical debt, issues with paying for healthcare and medical-debt collections all declined during the pandemic, according to the Urban Institute, but the inequities among races persisted. Among all racial and ethnic groups, Black adults reported the highest rate of medical debt in April 2021, followed by Hispanic adults and then white adults. Black Americans also reported the highest rate of medical debt in collections, followed by majority-American Indian adults, Hispanic adults and white adults.

The reality of medical debt is multilayered, said Berneta Haynes, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center. People who have defaulted on their loans or who are unable to pay their credit-card bills have the constant added stress of debt collectors contacting them, or they may even have their wages garnished or a lien placed on their home. Some may be pushed into risky alternatives, such as payday loans.

“Medical debt is special in one particular way — it’s unpredictable. You can’t plan for it,” Haynes said. “It is not necessarily anyone’s fault. You can’t necessarily determine when you’re going to get sick or injured. It’s not like taking out a mortgage or an auto loan.”

The true impact of the pandemic on medical debt is yet to be seen, Haynes said, but there is likely to be a negative effect when COVID-specific benefits and legislation expire.

Americans of all ages worried about contracting COVID at the height of the pandemic, but some were at higher risk of medical complications, such as older Americans and people with chronic health issues.

Black and Hispanic adults also tend to face more health challenges than some of their counterparts, said Tricia Neuman, executive director of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicare Policy, and a larger share of Americans on Medicare tend to be in poor health. “The pandemic took a harder hit on older Americans generally, and people of color specifically,” she said.

The value of financial advice

When attending large national conferences of financial planners with thousands of participants, Saundra Davis is usually one of about 100 Black women in attendance, she said. If those conferences were on the local level, she is often the only one.

As a professor of financial planning at Golden Gate University, she regularly sees the same trend in her classroom, with fewer people of color among her students. This can eventually trickle down to affect how retirement savers get their financial advice — or if they get it at all, she said.

It comes down to empathy, Davis said. “Judging people’s choices without understanding the nuance of their lives can do harm, and I think that’s the thing that gets overlooked in work like this,” she said. Davis is also the founder and executive director of Sage Financial Solutions, a nonprofit focused on providing financial education to underserved communities.

Having someone to turn to is important — especially in an economic environment where the market is volatile and inflation and interest rates are ticking upward — and prospective clients often need to feel that the professional they’re working with can empathize with the way they view money or how they use their money, she said.

Of the 535,000 personal financial advisers in the U.S. in 2021, 7.3% were Black, 7.5% were Asian and 7.7% were Hispanic or Latino, compared with 82.2% who were white, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Of course, clients and financial advisers don’t necessarily have to come from the same background to work well together. Davis’s financial planner is a white woman, one of the first professionals who welcomed her into the industry, and they have open conversations about Davis’s money-management style, she said. “If she says something about changing a behavior for me and it is cultural, I can say that to her and she gets it,” Davis said. “She doesn’t try to change my mind.”

One positive the pandemic has brought

The pandemic has been an unprecedented event in all of our lives. While it caused many setbacks for retirement savers, it also created circumstances for some Black Americans to create their own wealth through entrepreneurship, said Kiersten Saunders, a personal financial writer and co-author of “Cashing Out: Win the Wealth Game by Walking Away.”

Workers were able to spend more time — many while stuck at home — working on a passion project or taking in extra income through freelance and gig work. During the day they could work the jobs that gave them a regular paycheck and health insurance, and at night they could build their own businesses. “That wasn’t an option before the pandemic,” Saunders said.

Business owners suffered because of the pandemic, with many shops and restaurants having to shut their doors or scale back operations, but new businesses also flourished. Black owners made up 26% of those starting up microbusinesses during the pandemic, compared with 15% before March 2020, according to a Brookings Institution report. Comparatively, 60% of microbusiness owners were white after the pandemic began, versus 71% before. The boom in Black businesses could be partially attributed to stimulus checks, Andre Perry, a senior fellow at Brookings Metro, said during a Brookings virtual event about black businesses last year.

“This was an opportunity for the rising star, the new entrepreneur, to get a foot in the door and really, really prove themselves,” Segun Babalola, president of the St. Louis African Chamber of Commerce, said during the same Brookings event. “This pandemic actually was a blessing in disguise for some businesses.”